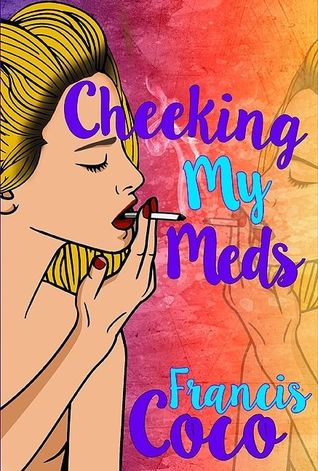

The Butchering Art:

Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine

By Lindsey Fitzharris

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017

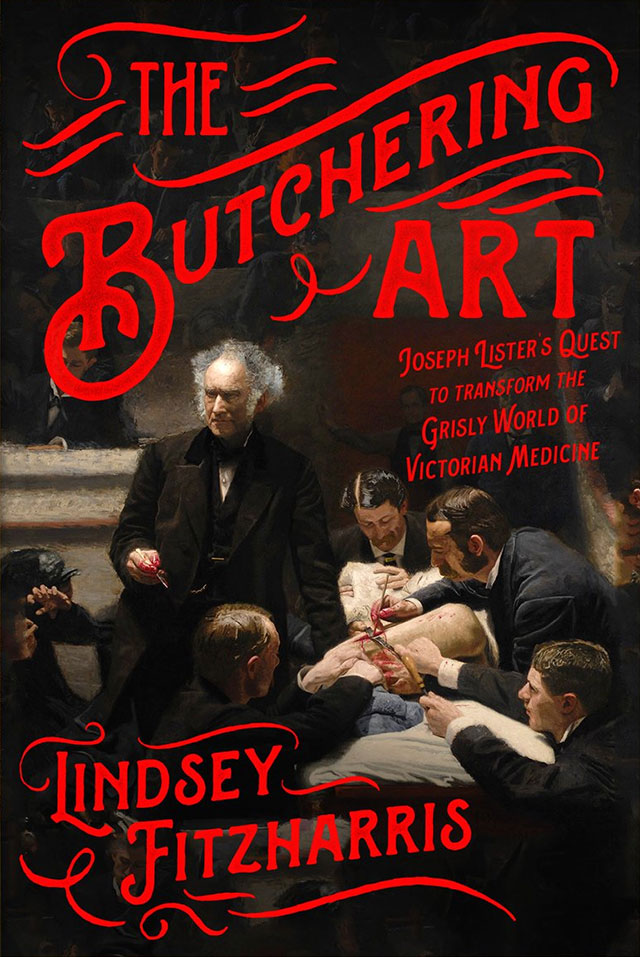

Speed and spectacle typified British surgery in the first half of the 19th century. The operating theater no doubt got its name from the audience it drew from curious laypeople right off the streets although naturally the first rows and floor area were crowded with medical students. A surgeon might not be able to operate until he had enough space. Frustrated audience in the back rows yelled, “Heads, heads!” when people in front obscured their view.

We forget the major impacts that our understanding—of science, medicine and technology, for instance—have had on culture. The Butchering Art reminds the reader that even such details as how people got hurt, how they endured large tumors over years of growth or operations for the same, and what they believed did and did not cause illness have radically altered. We would be shocked at what people argued about over the dinner table and at staff meetings!

Just before the mid-19th century, “Hospitalism” was a coined phrase understood to refer to the increase of infection and suppuration brought on by “the big four” killers in hospitals: gangrene, septicemia, “pyemia” (development of pus-filled abscesses) and erysipelas (a streptococcus infection of the skin, i.e. St. Anthony’s Fire).

Those in the medical field knew that hospitalism was a highly likely recurring event at large urban hospitals but they did not know why. Because infections were so prevalent in big hospitals, some doctors were proponents of patients being treated in their own homes or at the doctors’ offices. Understandably, however, it was easier for doctors to perform surgeries and for nurses to watch over patients in big hospitals, but within those confines, medical staff argued about how contagion spread, giving rise to two groups—“contagionists” and “anti-contagionists.”

Contagionists believed in contagion that went from person to person. Contagionists had an assortment of theories, including invisible bullets of disease. Anti-contagionists indignantly pointed to the squalor of the living conditions of the poor as well as the disgusting state of streets in large urban areas (London) Miasma was blamed for the spread of disease.

Set against this background of ideas comes Joseph Lister, upon whose life Lindsey Fitzharris brings her own microscope study upon the life of Joseph Lister, the British surgeon of Quaker background who was noted (and knighted) for his studies and promotion of antiseptic surgery and sterilization. However, in The Butchering Art, the author begins with Robert Liston, who was noted for his speed and dexterity, if not for the survival rate of patients (poor at best) due to the fact that no one yet understood how infection occurred. Since there was nothing to render the patient unconscious either, the best surgeons were fast. Liston, Fitzharris tells us, “could remove a leg in less than thirty seconds.” Speed had its drawbacks, as when Listen sliced off the testicle along with the leg being amputated.

Joseph Lister, as it happens, was witness to Liston’s use of ether, giving rise to the claim that patients would not suffer pain during surgery. There was still nothing yet that could prevent their falling prey to infection, which was expected. Pus was part of the healing process, but the healing process often led to death.

This fascinating book held me in its grip. Fitzharris does a wonderful job of coloring in the concepts of the culture, depicting the smells and images of England and Scotland, all while demonstrating that there was both wondrous good and nearly insurmountable ego involved in the medical profession—and either trait could kill a person as easily as cure. How a surgeon like Lister ever got the rest of the medical field to listen, (for there is hardly any profession less proud than that of surgeons) when the principles he applied saved lives put others in his shadow, is a true marvel. #TheButchering Art #NetGalley @fsgbooks

Available on Amazon Kindle and Nook.

Available on Amazon Kindle and Nook. How our parents treat us when we are young shapes our worlds and morale. Francis Coco visits this theme in her astonishing revelations of an adolescent girl—herself—committed in the 1980s to a psychiatric hospital for teenagers. Her voice is fresh and endearing; she wears her heart on her sleeve and describes the truth without flinching.

How our parents treat us when we are young shapes our worlds and morale. Francis Coco visits this theme in her astonishing revelations of an adolescent girl—herself—committed in the 1980s to a psychiatric hospital for teenagers. Her voice is fresh and endearing; she wears her heart on her sleeve and describes the truth without flinching.