I was sitting in the Home Depot parking lot on Sunday (January 26) around 11 a.m. when I got a text from my youngest daughter, Katie. “Aww, Kobe died.” I stared at it a moment, then opened a news app on my phone and saw the headline about the helicopter crash. Then a bit later the added news that his second oldest daughter, Gianna, was with him. And still later yet, the news that two other families with the Bryants had suffered horrible losses as well.

It’s awful. Tragic. Unfair. But that’s not what I wanted to write about today. I have spent the past 48 hours watching numerous tributes on television, watching some of his best games, and reading so many well written memories from people who knew Kobe. There is nothing I could say here that would compare to those, so I am going to share the personal impact he had on my life with whomever might be interested.

I hated Kobe when he first came into the league because I lived in the Seattle area at the time, and was a huge Seattle Supersonic fan. Back then, Gary Payton was my guy. Tough-nosed, hard working, one of the best point guards to ever play in the NBA. So in retrospect I guess I didn’t hate Kobe in particular, just that the Lakers were direct competition and Kobe was their new rising star.

I moved to Fresno in 2002, but remained a Sonic fan until they traded Gary to Milwaukee. Unforgivable! How could they? So, I decided I had to find a new team. And given Fresno’s location, that meant I could choose one of three teams in my new state. So I went with the Lakers, the team I used to follow way back in the Magic Johnson era. Needless to say, I haven’t been disappointed. Three straight finals appearances, winning back-to-back titles in 2009 and 2010. And at the heart of those great seasons, Kobe. The day I went from somewhat grudgingly admitting he was a major talent to realizing he might be the best ever (at least in my lifetime of following the NBA) was on January 22, 2006. The night he scored 81 points. For those who don’t realize how difficult that is in a professional basketball game, only one player has ever scored more in the league’s 73 year history. Wilt Chamberlain did it on March 2, 1962, scoring an amazing and probably never to be seen again 100 points.

I could go on and on about Kobe’s greatness on the basketball court, but what set him apart for me was his total devotion to the game. A work ethic like no other. He wouldn’t quit. The night he suffered the dreaded Achilles tear on April 12, 2013 provides the best example. Again, for those who don’t know, that injury is among the most dreaded in the sport’s world. It takes a year or more to recover, and most players are never the same if they do make it back. I have seen it happen on the court numerous times, and each time players are always taken off the court on a stretcher. Not Kobe. He had been fouled prior to his fall, so he had two free throws coming. Rather than allow the opposing team to select someone from off the bench (which would, according to NBA rules, keep Kobe from returning to the game), he got up, walked under his own power to the free throw line, stood there and made both, then walked off the court, again under his own power, and on to the locker room. The pain must have been unimaginable. But that was Kobe. Always the competitor. Always defying the odds. He was probably hoping the trainers could do something to fix him up so he could come back into the game.

Kobe came back from that injury and played through the 2015-16 season. And when he decided to end his NBA career at age 37, he went out by scoring 60 points in his final game. And then, with a smiling thank you to his fans and a wave goodbye, he moved on. He pursued other interests and became just as successful off the court as on. Most notably though, he excelled at being a dad to his four beautiful daughters. On the day he died, he was on the way to daughter Gianna’s AAU basketball game. Gianna shared her father’s love for the game, something that must have given him such pride and joy.

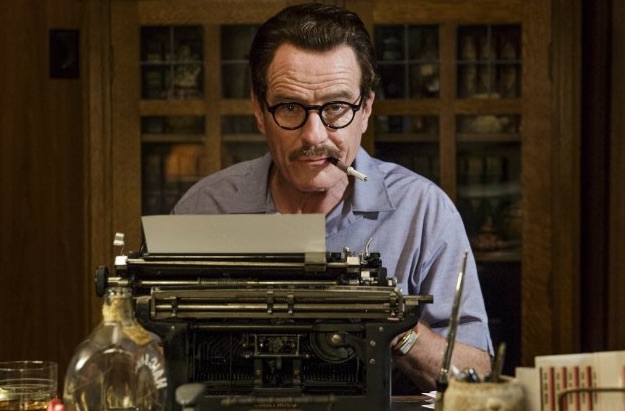

Kobe’s never quit attitude stuck with me insofar as my writing pursuits were concerned. I wrote and sold a book on the NBA (Hoop Lore) despite doubters telling me it wasn’t likely a white woman who had never played the game would be able to author let alone sell such a work, given how the sport is dominated by African-American men. Hoop Lore wasn’t a massive bestseller but I am proud of it just the same. Being able to write about something I feel so passionate about and have others in the field accept it as a bona fide piece of work is every writers dream.

But it’s an undeniable fact that writing and selling your work is a lot more difficult than when I sold Hoop Lore, which was published in January 2007. Amazon and other online books sites are great for people who want to post their work while bypassing conventional publishers. Frankly, that is the only way that most people will ever get their work out there today, myself included. Publishers want sensationalized celebrity stories or works by authors they already know, or once in a while, a book that just hits a niche people were looking for. They don’t have the time or resources for much of anything else.

And I’m OK with that. Like Kobe, I have other interests I want to pursue. I also have a book idea or two that I may end up writing in the future. Or maybe not. Meanwhile, I have been enjoying other creative activities, most notably building things. I made an heirloom rocking chair for my grandson, a toy box, and a custom rocking chair designed from scratch for my granddaughter. Future endeavors will probably include a doll house, some bookcases, and another toy box. In between those projects, our house has turned into a small animal shelter with four dogs and two cats. I also enjoy feeding the squirrels and birds in our yard. Oh, and yes, I love to garden – a hobby I picked up from my great grandmother when I was a small child. I owe Kobe a big thank you for showing me that it’s fine to move on to other ventures and not feel bad or guilty about doing it. I’m 63 now, and still enjoying life! Thanks for the memories and inspiration Kobe, I will always love you! RIP.

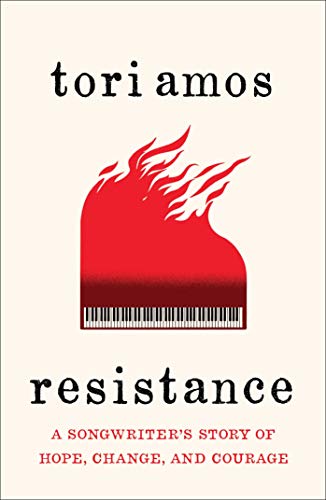

Tori Amos first pierced my consciousness like a lightning bolt thrown by Letterman from his Late Night Show. That might sound mundane except that I was in Saudi Arabia, married to a Saudi, and this dynamic, creative & intellectual singer on a Western TV show (one that made it past the censors) pulled me up to the edge of my seat with her voice and thoughts, melodic yet dissonant, haunting and probing. Her creative expression embodied the reason I was in the Middle East and in the same musical breath, straight from the diaphragm, that creativity (like critical thinking, scientific investigation, and freedom to make life choices) was so fragile an acquisition for women anywhere that it has to be guarded and nurtured, not used and then suffocated. I was acutely reminded of these memories as I moved into the pages of this important memoir with the spot-on title. Resistance is a recounting of how a conscientious and vibrantly switched on singer-song writer finds purpose. Resistance is about being alive to meaning; it is about music being the meeting place where thinking people can cut through propaganda to try to understand what is really going on in the world.

Tori Amos first pierced my consciousness like a lightning bolt thrown by Letterman from his Late Night Show. That might sound mundane except that I was in Saudi Arabia, married to a Saudi, and this dynamic, creative & intellectual singer on a Western TV show (one that made it past the censors) pulled me up to the edge of my seat with her voice and thoughts, melodic yet dissonant, haunting and probing. Her creative expression embodied the reason I was in the Middle East and in the same musical breath, straight from the diaphragm, that creativity (like critical thinking, scientific investigation, and freedom to make life choices) was so fragile an acquisition for women anywhere that it has to be guarded and nurtured, not used and then suffocated. I was acutely reminded of these memories as I moved into the pages of this important memoir with the spot-on title. Resistance is a recounting of how a conscientious and vibrantly switched on singer-song writer finds purpose. Resistance is about being alive to meaning; it is about music being the meeting place where thinking people can cut through propaganda to try to understand what is really going on in the world.

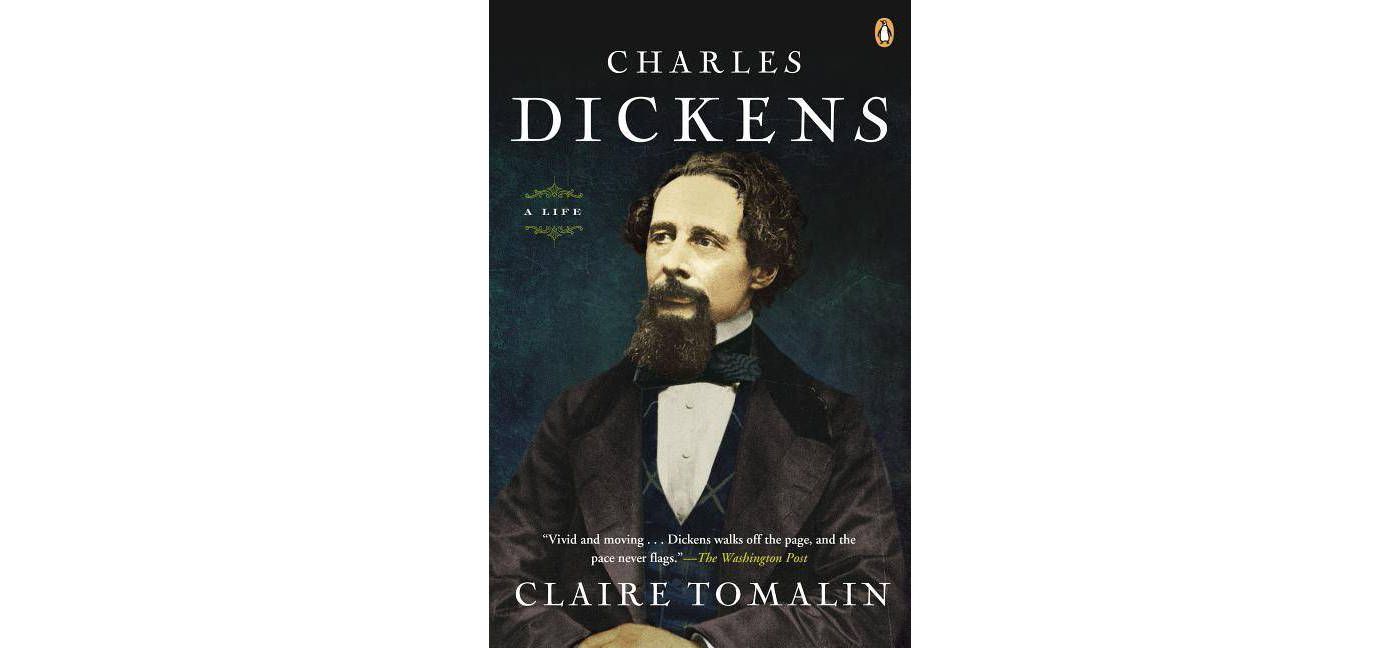

I am almost at the end of Claire Tomalin’s biography of Charles Dickens–again. The first time, I bought the hardback and read it with my eyes. What stuck in memory was the great British author’s complaint of being chained to his desk or table in order to complete a novel. Any writer can relate, even we the unknown. Another sticky detail, like a shred of carrot or pumpkin seed in my teeth, was the worshipful obsession from the American public. Individuals would snip of bits of his fur trim. I refuse to look back at the book itself to see if I am right or wrong about this remembrance because this is an experiment. Same book, same reader, different experiences.

I am almost at the end of Claire Tomalin’s biography of Charles Dickens–again. The first time, I bought the hardback and read it with my eyes. What stuck in memory was the great British author’s complaint of being chained to his desk or table in order to complete a novel. Any writer can relate, even we the unknown. Another sticky detail, like a shred of carrot or pumpkin seed in my teeth, was the worshipful obsession from the American public. Individuals would snip of bits of his fur trim. I refuse to look back at the book itself to see if I am right or wrong about this remembrance because this is an experiment. Same book, same reader, different experiences.

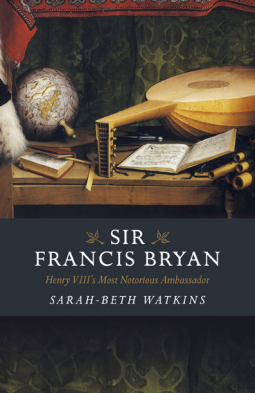

Hooray for this nonfiction about Sir Francis Bryan, diplomat for King Henry VIII; this book stands out for the way in which Watkins makes the characters feel truly human, piquing the readers’ interest in their traits and foibles. It was super interesting to read about how Wolsey tried to pry the king’s friends away from Henry. Keeping a young man away from his male friends? It is also fascinating to read about the meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, where Francis I, though subservient in some respects to Henry, beat him in a wrestling match. Somehow, Henry held his temper. Francis I spent about 40 thousand pounds and Henry 36 thousand on this event, which Watkins gives as 32 million pounds sterling in today’s money. Good grief! Despite my mentioning Henry so often, I was really attracted to the way the author described the king’s friends, the way they dressed, and how they acted with each other. I truly enjoyed following the path of Sir Francis Bryan. The vicissitudes of life are thrown into high throttle in this milieu–one could gain the world one day and die a bloody mess (or drown attired in full armor) the next. A lot of detail is in this book about the Howard family, which I found interesting, knowing an American descendant of that same family. Bryan was an incredibly dexterous man, both physically and mentally, matching the needs of his king without getting into the kind of trouble that could cost his estate or his life. When he was on off hours, he drank and gambled too much, but that makes him human! I found myself envying him for knowing the courts of his era so well that he could compare them easily. He makes the most engaging comments: “And in the French Court I never saw so many women; I would I had so many sheep to find my house whilst I live” [sic]. I have never seen a book that gives more interesting details–perhaps as good, but never better. Yes, he lost his eye in a jousting match and apparently it is for that reason that it is nigh impossible to find a portrait of him. He was too embarrassed to leave a painting for posterity with his eye patch. I think I may end up buying the hard cover of this fascinating book. I just reviewed Sir Francis Bryan by Sarah-Beth Watkins. #SirFrancisBryan #NetGalley #ChronosBooks

Hooray for this nonfiction about Sir Francis Bryan, diplomat for King Henry VIII; this book stands out for the way in which Watkins makes the characters feel truly human, piquing the readers’ interest in their traits and foibles. It was super interesting to read about how Wolsey tried to pry the king’s friends away from Henry. Keeping a young man away from his male friends? It is also fascinating to read about the meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, where Francis I, though subservient in some respects to Henry, beat him in a wrestling match. Somehow, Henry held his temper. Francis I spent about 40 thousand pounds and Henry 36 thousand on this event, which Watkins gives as 32 million pounds sterling in today’s money. Good grief! Despite my mentioning Henry so often, I was really attracted to the way the author described the king’s friends, the way they dressed, and how they acted with each other. I truly enjoyed following the path of Sir Francis Bryan. The vicissitudes of life are thrown into high throttle in this milieu–one could gain the world one day and die a bloody mess (or drown attired in full armor) the next. A lot of detail is in this book about the Howard family, which I found interesting, knowing an American descendant of that same family. Bryan was an incredibly dexterous man, both physically and mentally, matching the needs of his king without getting into the kind of trouble that could cost his estate or his life. When he was on off hours, he drank and gambled too much, but that makes him human! I found myself envying him for knowing the courts of his era so well that he could compare them easily. He makes the most engaging comments: “And in the French Court I never saw so many women; I would I had so many sheep to find my house whilst I live” [sic]. I have never seen a book that gives more interesting details–perhaps as good, but never better. Yes, he lost his eye in a jousting match and apparently it is for that reason that it is nigh impossible to find a portrait of him. He was too embarrassed to leave a painting for posterity with his eye patch. I think I may end up buying the hard cover of this fascinating book. I just reviewed Sir Francis Bryan by Sarah-Beth Watkins. #SirFrancisBryan #NetGalley #ChronosBooks