Dostoevsky in Love by Alex Christophi

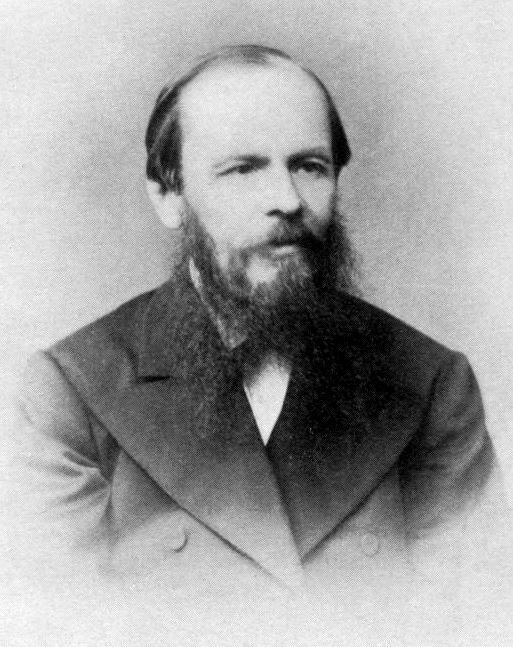

You might have heard of Dostoevsky—might have decided to read one of his novels—but if you haven’t read one or have only just learned his name, know that Dostoevsky is considered one of the most representative writers of 19th century Russia in the same way that Charles Dickens is considered one of the most representative writers of 19th century Great Britain and the English-reading world. They both focused on the poor and the dispossessed in their literature, insisting on the humanity of the downtrodden, and through characters and circumstances presented, both writers helped give recognizable qualities to national identity.

The title of this book may have the potential reader thinking it is about Dostoevsky’s romantic life, but it is about so much more. It is about his love of life, mankind, philosophy, God and literature as well as his driving passion to understand why he was dealt the circumstances he and the rest of his nation lived in. He was quite honestly in love with Russia. Though he enjoyed inexpensive (then) places to live and write like Switzerland, he always felt the need to be in the most dynamic centers of Russia.

When Fyodor Dostoevsky was little, his father, a hard-working doctor, was recognized for zealous medical service, for which he was awarded the Order of St Anna. This recognition by the government lifted the family from its poverty to a position at which they could afford to hire staff—a coachman, cook, maid and nanny. The boost up the hierarchical caste system placed the family at the lowest level of gentry and gave the family rights that people in the free world take for granted. I paused every time I read that Dostoevsky or his family gained a right or permission because the situation reminded me of almost two decades living in a monarchical autocracy, where I could not work or own property or inherit (due to being a foreigner). Similarly, 19th century Russia had (and many other countries today still have) a far different societal system than what is familiar to Western readers. The Order of St. Anna bestowed upon Dr. Dostoevsky gave him the right to purchase land and own his own place. Before that, he could only rent. Still, gentry could go into debt, which fate befell both Dr. Dostoevsky and his son after him. In (Fyodor’s case, however, much of the debt was senselessly self-inflicted.)

The reader must imagine that the child, Fyodor, and his brother Mikhail, would have been thrilled by the rise up the ladder and proud of their father for achieving the recognition that made them gentry. That career boost probably created a sense of gratitude towards the tsar in Dostoevsky, which helps to explain why Russians had a hard time trying to figure out what side Dostoevsky was on—that of the poor or the ruling elite. Like Dickens, he knew people on both sides of the train tracks, but the Russian writer could be said to have suffered far more than the British. Dostoevsky’s mother died of tuberculosis when he was a teen and the family broke apart, just like that. Dostoevsky showed his love of literature early and belonged to a group that discussed books critical of tsarist Russia for which he was sentenced to many years in a Siberian prison camp and then more years of military service in exile. His sufferings seemed to have known no bound. I read about them with a cold hand gripping my intestines, wondering how he could possibly have endured all he did and still have found love and acclaim.

But he managed, with his latter marriage being a happy one and his years of literary endeavor bringing him the kind of recognition every writer dreams of—with all kinds of misery filling the gaps. Even the most dedicated reader of literary greats will wonder whether Dostoevsky did not arrive at good luck through sheer happenstance, for he lived in a political climate with nothing but traps and holes. This is the kind of book that will have readers rummaging through the end notes, sorry there is not more to read. I adored the comments about the influence of Dostoevsky’s writing after his death.